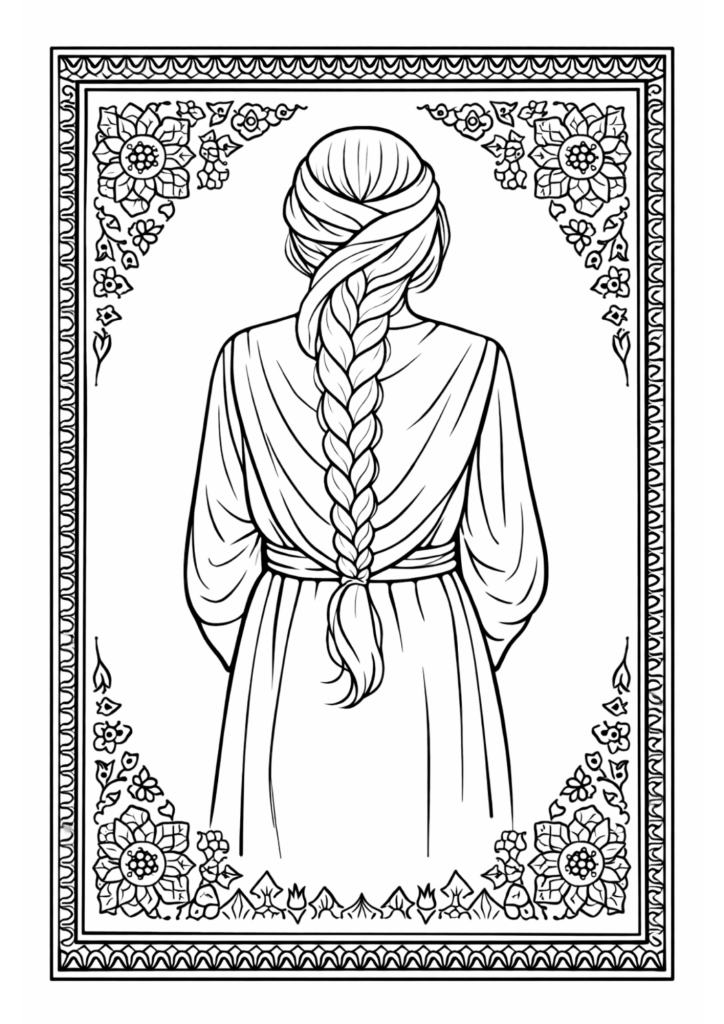

Our braids, kezî, are not simply a hairstyle.

Historically, long braided hair has marked womanhood, and belonging.

The braid carries memory across generations.

Mothers braid daughters’ hair. Sisters braid each other’s.

It is an intimate, everyday act through which identity,

and culture are passed.

In Kurdish tradition, hair also carries emotional and moral weight.

Cutting one’s hair is an act of mourning, a visible sign that

something irreversible has happened. Because of this, touching or

cutting a woman’s braid without consent has always been understood

as a violent violation, not a neutral gesture.

This understanding has resurfaced powerfully in recent days.

Across Kurdish regions and the diaspora, women are

openly reclaiming the braid as a symbol of dignity and resistance.

When images circulated of a Kurdish woman’s braid being cut by

violent men in Syria, the response was immediate and collective.

Women are posting photos/videos of their own braids on social media.

The message repeated again and again is clear

for every braid cut, thousands will grow.

Within Jineology, the Kurdish women’s science, the braid is

understood not as decoration but as embodied knowledge.

Jineology centers women’s lived experience as a source of truth

and history. In this framework, the braid becomes a site where body,

memory, and political reality intersect. The body is not separate from resistance. Culture is not separate from struggle.

Braiding hair is therefore not passive or nostalgic.

It is an active act of defiance. A refusal to be erased.

A refusal to let violence redefine women and freedom.

Kezî holds grief, yes. But it also holds persistence.

It says we are still here. And we remain connected.